More than 88 million adults in the U.S. have prediabetes, a condition that not only increases the risk of developing type 2 diabetes, but also has profound health impacts that can complicate other cardiometabolic diseases.

What is prediabetes?

As with type 2 diabetes (T2D), prediabetes increases the risk for atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD), nephropathy, retinopathy, and many other serious conditions. The exponential rise in obesity has contributed to the overall impact of prediabetes; individuals with prediabetes who are also overweight or obese have an increased risk of their disease progressing to T2DM. To offset these alarming trends, comprehensive efforts are required to prevent both the onset and progression of T2DM and its precursor, prediabetes.

Prediabetes prevalence

Despite increased morbidity and mortality, prediabetes is underdiagnosed and undertreated. It is estimated that 90% of individuals with prediabetes in the U.S. are not aware that they have the condition. Treating prediabetes is a complex and controversial topic in the clinical community, with many clinicians being reluctant to screen and manage patients with prediabetes. Ambiguity about screening criteria, the shortage of approved treatments, and lack of awareness have stalled efforts to manage prediabetes in clinical practice. However, several approaches to prevent or reduce diabetes progression in these individuals have been successful, including targeting overweight and obesity with lifestyle interventions, metabolic surgery, or pharmacotherapy. Significant data and advances suggest that now more than ever, we have appropriate tools to target the burden of prediabetes.

Prediabetes screening recommendations

Surveys of primary care physicians that treat patients with a high risk of developing diabetes have shown significant gaps in screening practices, including lack of awareness about screening guidelines and risk factors. Significant disagreement was reported in how clinicians view prediabetes as a clinical entity, with those that had a more favorable view of prediabetes more likely to follow guidelines for screening compared to participants with a less favorable view of prediabetes.

Prediabetes is characterized by blood glucose levels that are higher than normal, but not high enough to be diagnostic for T2DM. The criteria for prediabetes are based on impaired fasting glucose, impaired glucose tolerance, or slightly elevated HbA1c, as defined by the American Diabetes Association and the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists, which are the organization guidelines most commonly used in the U.S.

Clinical management of prediabetes

Addressing prediabetes is not only beneficial for glycemic control, but also for decreasing overall cardiometabolic burden, which is often high in patients with prediabetes, as well as decreasing the risk of developing micro-and macro-vascular complications. Several approaches have been successful, including intensive lifestyle modifications, metformin, metabolic surgery and more recently, newer obesity pharmacotherapy.

Metformin and lifestyle interventions for prediabetes

One of the main goals of prediabetes management is weight loss, and some of the strongest evidence for lifestyle modifications in the prevention of diabetes comes from the Diabetes Prevention Program (DPP) established by the CDC to bring evidence-based lifestyle change programs to Americans at high risk for T2DM. In this program, non-diabetic patients with impaired glucose tolerance or elevated fasting plasma glucose were randomized to metformin, a lifestyle modification program (with goals of at least a 7% weight loss and at least 150 min of physical activity per week), or placebo to assess whether these interventions would prevent or delay the development of diabetes. The lifestyle intervention reduced the incidence of diabetes by 58% and metformin reduced the incidence by 31% compared to placebo. The baseline body mass index was 34.0, and during the trial, participants in the lifestyle arm lost an average of 5.6 kg, compared to 2.1 kg and 0.1 kg weight loss in the metformin and placebo groups, respectively.

Similar programs to the DPP have been implemented successfully in several other countries (China, Sweden, Finland, India, and Japan), and based on this evidence, intensive behavioral lifestyle modeled after DPP or metformin (especially for patients with a BMI ≥35 kg/m2) now form the foundation of prediabetes treatment as recommended by ADA and AACE.

Metabolic surgery

Many studies have highlighted the impact of bariatric surgery on T2D, such as: reduction of insulin resistance; favorable changes in gut hormones; bile-acid signaling; improvement in gut microbiome composition; transport of glucose and utilization of glucose by the gut; favorable changes in sensing in the proximal intestine that renders increases in insulin sensitivity; and changes in iron metabolism that might confer unexpected benefits on glucose homeostasis. A range of bariatric surgery interventions has shown efficacy in diabetes prevention, including the Swedish Obese Subjects study, Restoring Insulin Secretion Consortium study, and others. Given that metabolic surgery produces significant weight loss, it can be a consideration for patients with prediabetes and comorbid obesity.

Existing, new, and emerging drug therapies

Because the challenges of adhering to an intensive lifestyle regimen are well recognized – the 15-year follow-up of DPP reduction of diabetes incidence fell to 27% with lifestyle therapy and 18% with metformin – the addition of weight-loss pharmacotherapy or bariatric surgery may be necessary to treat prediabetes, particularly in high-risk patients. Several studies have evaluated a multitude of existing diabetes therapies in this setting, including thiazolidinediones, as well as other conventional obesity medications such as orlistat, phentermine/topiramate, and lorcaserin. However, safety concerns have limited the potential long-term use of these agents for diabetes prevention.

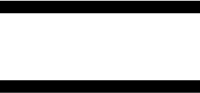

There is promise for treating prediabetes with glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists (GLP-1 RAs). Currently, two GLP-1 RAs are approved for the management of obesity: liraglutide 3.0mg and, more recently, semaglutide 2.4mg. These drugs have several physiological effects on glycemic and weight control – they increase insulin secretion, suppress glucagon secretion, slow gastric emptying, and increase satiety. Due to these combined actions, GLP-1 RAs can improve obesity and the pathogenesis of declining pancreatic beta-cell function. Across cardiovascular outcomes trials, GLP-1 RAs have been shown to improve glycemic control, with the added benefits of weight loss and decreased hypoglycemia, as well as cardiovascular (and potentially renal) benefits, albeit mostly in patients with T2D.

Key takeaway

Growing evidence supports comprehensive lifestyle and interventional approaches as the best means to prevent the development of several prediabetes-related complications. These advances indicate that the conversation around treating prediabetes should be shifted towards thinking about decreasing overall cardiometabolic burden and preventing cardiovascular complications.

References:

- Abbasi, Jennifer. “Semaglutide’s Success Could Usher in a “New Dawn” for Obesity Treatment.” JAMA2 (2021): 121-123.

- Al Rifai, Mahmoud, and Michael D. Shapiro. “A multifaceted approach for management of prediabetes and its associated cardiovascular risk.” Diabetes/metabolism research and reviews6 (2020): e3314.

- Ali, Mohammed K., et al. “Cardiovascular and renal burdens of prediabetes in the USA: analysis of data from serial cross-sectional surveys, 1988–2014.” The Lancet Diabetes & Endocrinology5 (2018): 392-403.

- American Diabetes Association. “2. Classification and diagnosis of diabetes: Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes—2022.” Diabetes CareSupplement 1 (2022): S17-S38.

- Bowen, Michael E., et al. “Building Toward a Population-Based Approach to Diabetes Screening and Prevention for US Adults.” Current diabetes reports11 (2018): 104.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). “Diabetes and prediabetes.” Available at https://www.cdc.gov/chronicdisease/resources/publications/factsheets/diabetes-prediabetes.htm, accessed January 14, 2021.

- Das, Sandeep R., et al. “2020 expert consensus decision pathway on novel therapies for cardiovascular risk reduction in patients with type 2 diabetes: a report of the American College of Cardiology Solution Set Oversight Committee.” Journal of the American College of Cardiology9 (2020): 1117-1145.

- DeJesus, Ramona S., et al. “Incidence rate of prediabetes progression to diabetes: modeling an optimum target group for intervention.” Population health management3 (2017): 216-223.

- Dixon, Dave L., and Salvatore Carbone. “Screening, identification, and management of prediabetes to reduce cardiovascular risk: A missed opportunity?.” Diabetes/metabolism research and reviews6 (2020): e3316.

- Echouffo-Tcheugui, Justin B., and Elizabeth Selvin. “Prediabetes and what it means: the epidemiological evidence.” Annual Review of Public Health42 (2021): 59-77.

- Garber, Alan J., et al. “AACE/ACE comprehensive diabetes management algorithm 2015.” Endocrine Practice4 (2015): 438-447.

- Grundy, Scott M. “Pre-diabetes, metabolic syndrome, and cardiovascular risk.” Journal of the American College of Cardiology7 (2012): 635-643.

- Mainous, Arch G., et al. “Prediabetes screening and treatment in diabetes prevention: the impact of physician attitudes.” The Journal of the American Board of Family Medicine6 (2016): 663-671.

- Perreault, Leigh, et al. “81-OR: Once-Weekly Semaglutide 2.4 mg Improved Glucose Metabolism and Prediabetes in Adults with Overweight/Obesity in the STEP 1 Trial.” (2021).

- Perreault, Leigh. “Prevention of Type 2 Diabetes.” Diabetes and Exercise. Humana Press, Cham, 2018. 17-29.