Introduction

Obesity and type 2 diabetes (T2D) are closely related; more than 90% of people with T2D also have overweight or obesity and more than 20% of people with obesity also have T2D [1]. Obesity is one of the main modifiable risk factors for diabetes and adverse cardiovascular events, the latter being the leading cause of mortality in patients with T2D [2]. In fact, the rise in the prevalence of both diabetes and obesity is a global health challenge and it has been estimated that 60-80% of people with diabetes have a body mass index (BMI) of ≥30 kg/m2 [3]. The co-occurrence of diabetes and obesity, now commonly termed “diabesity,” a new worldwide epidemic.

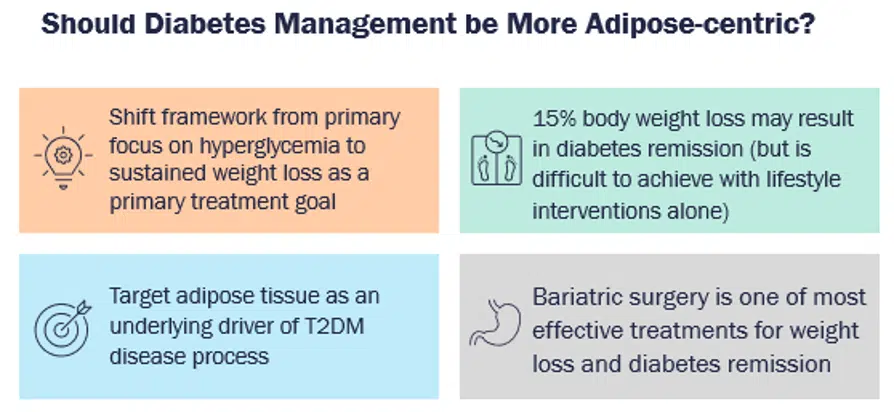

Several studies have corroborated the fact that weight loss can be an effective strategy to mitigate the risk of obesity-related comorbidities, including risk of T2D and cardiovascular mortality, leading to improvements in lipid profile, blood pressure, severity of obstructive apnea, and health-related quality of life [4]. In fact, weight loss of as little as 5% in people with diabetes can improve cardiometabolic risk factors, and a weight loss of more than 10% can reduce cardiovascular morbidity and mortality, as demonstrated in the LOOKAHEAD study [5]. This leads to a very pertinent and widely discussed question — whether the management of diabetes should be more adipose-centric, or whether obesity management should be a primary treatment target for patients with T2D [6].

Inertia and Challenges in Obesity Management

In the last decade, several studies have shown that many clinicians perceive obesity as a social and behavioral issue brought on by poor lifestyle choices [7-9], and most reported feeling unprepared for their medical training when it comes to treating patients with overweight, with some believing that treating obesity is “futile” [8,9]. As such, it is not surprising that providers still incorrectly document or screen for obesity, and that recognition of obesity as a disease remains low, including in patients with T2D. Consequently, although obesity prevalence is increasing, diagnostic rates remain low [10-13].

Establishing obesity as a disease is often the first step to improving outcomes, however, clinicians often do not know how to approach and initiate the conversation about obesity management with their patients [14,15]. Surveys have demonstrated that in obesity-related consultations clinicians often think that being overweight is not a serious issue or even worse, they tend to judge their patients and fail to motivate them to adhere to weight-loss strategies [14,15]. Patients reported that clinicians offered banal advice assuming that the patients were unhealthy or were not trying to address their weight, and assumed that other health symptoms were due to obesity without a proper medical history or examination [14]. Much of the inertia can be attributed to clinicians being busy treating other chronic diseases, lack of comfort with prescribing weight-loss interventions, and misconceptions about the efficacy and safety of pharmacological and other intensive approaches for treating obesity.

Many studies have underscored the advantages and the impact of lifestyle modifications on weight loss. Improving diet and physical activity can lead to a typical reduction of weight by 5% – 10%, which as mentioned above can have significant benefits on outcomes; however, these changes are difficult to maintain and weight regain is common [16,17]. According to Cardiometabolic Health Congress expert faculty, Jennifer B. Green, MD, professor of medicine at Duke University School of Medicine:

“While losing weight, our brain has kind of a weight-happy place and when we move away from that, our brain is unhappy and alters hormone levels to counteract it, so our body makes it more difficult to continue to lose weight once we’ve started losing and unfortunately, it tends to make us regain the weight back.”

This is supported by studies showing that the hunger hormone ghrelin increases with weight loss, and leptin – which helps prevent hunger and regulate energy balance – decreases with weight loss [18]. Meta-analyses have shown that approximately 50-80% of weight lost is generally regained within 3-5 years and it is harder, especially for people with T2D, to lose weight only with lifestyle changes. As such, it is pertinent to consider or add anti-obesity medications as adjunct to lifestyle therapy in people with weight-related complications (including uncontrolled diabetes), those who have difficulties losing weight with lifestyle therapy, or who have experienced weight regain following initial success on lifestyle therapy alone [19].

Guidelines for T2D Therapy When Weight is a Primary Concern

The treatment guidelines for T2D from the American Diabetes Association (ADA) have undergone significant paradigm changes in recent years, and have prioritized the individualization of therapy according to patients’ needs and comorbidities [20]. These guidelines advise that when choosing glycemic-lowering medications for patients with T2D and overweight or obesity, the effect of medications on weight should be considered, and clinicians should minimize or avoid using medications that are associated with weight gain whenever possible [20].

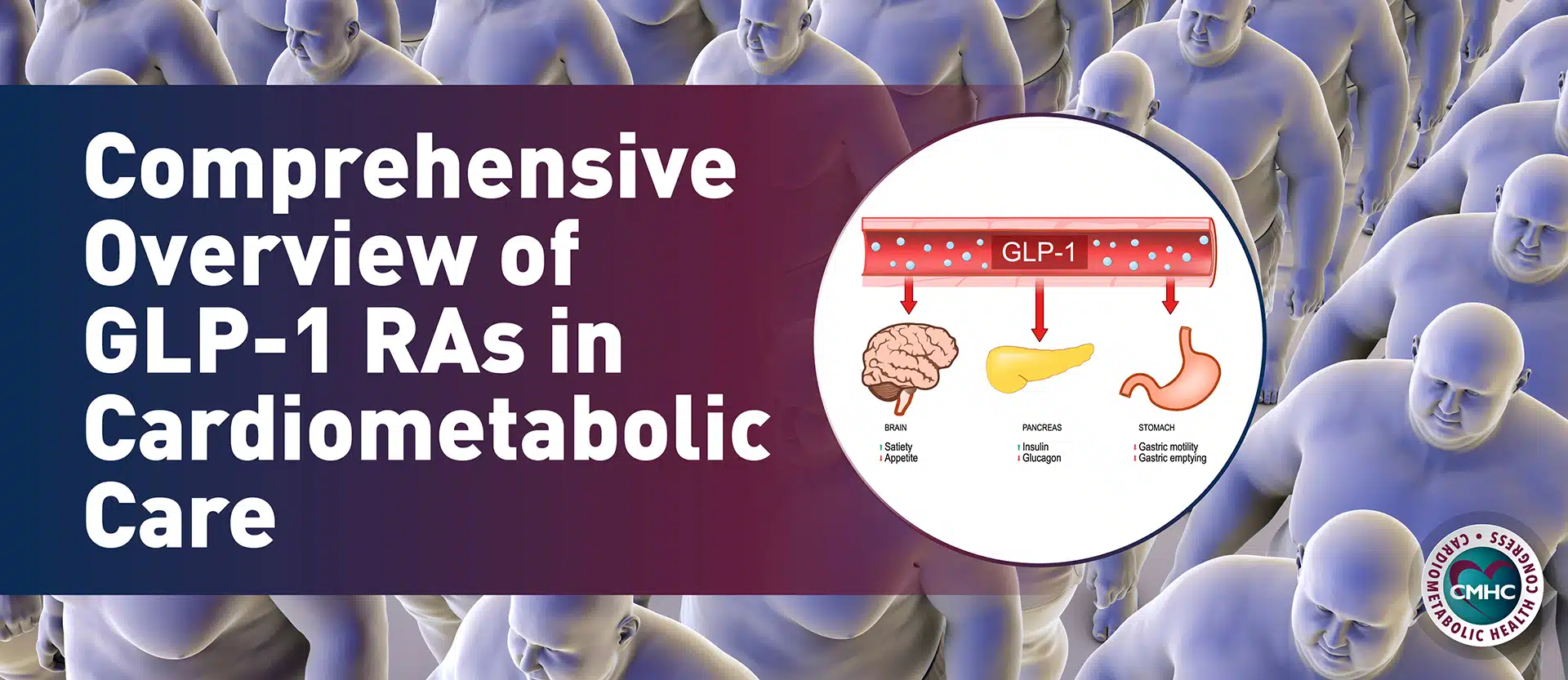

The 2022 ADA guidelines also have a section dedicated to the treatment algorithm for T2D when there is a compelling need to minimize weight gain or weight loss, suggesting that a glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonist with good efficacy for weight loss or a sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 (SGLT-2) inhibitor be considered if first-line therapy with metformin and lifestyle modifications did not lead to adequate glycemic control in the patient [20]. In patients with T2D who need their treatment regimen intensified to include injectable therapy, the guidelines now recommend considering a GLP-1 receptor agonist in most patients prior to initiating insulin therapy [20].

Available Anti-Obesity Medications

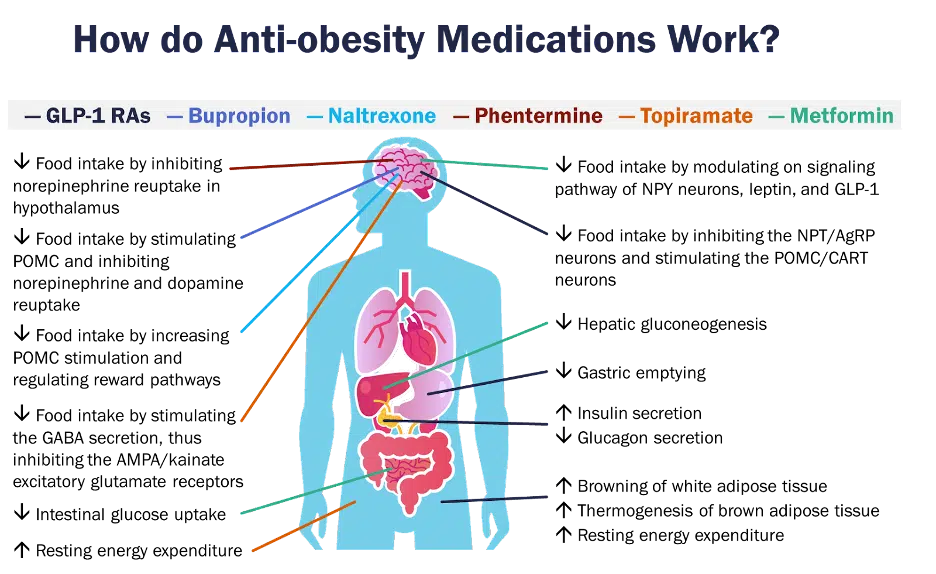

Several drugs are currently approved for the treatment of obesity, including phentermine, orlistat, phentermine/topiramate, naltrexone/bupropion, and two GLP-1 receptor agonists — liraglutide 3.0mg and semaglutide 2.4mg [21, 22]. They are all indicated for individuals with a body mass index (BMI) of ≥30 kg/m2 or BMI ≥27 kg/m2 with at least one adiposity-related disease. Of these, phentermine is only approved for short-term use (12 weeks) [21]. Of note, lorcaserin, which was previously approved for long-term obesity management, was withdrawn from the market in 2020 for a safety issue related to increased cancer incidence [22].

Throughout clinical trials, these drugs have demonstrated efficacy for weight loss, as well as additional benefits in certain cases, including lowering the risk of diabetes, improving glycemic outcomes, and cardiovascular risk [21, 22]. Most of these drugs essentially exert central effects to help reduce the stimuli to eat and facilitate weight loss. In addition, GLP-1 receptor agonists have some extra noncentral mechanisms for weight loss, as well as potentially metformin [22].

In 2021, a new GLP-1 receptor agonist, semaglutide 2.4mg, was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the management of chronic obesity. As the first drug approved for this indication since 2014, semaglutide has been deemed “practice changing,” since it showed a reduction in body weight of approximately 15-18% across four phase 3 trials [23]. Its approval was based on the positive results from the STEP (Semaglutide Treatment Effect in People with obesity) trials for weight management in people with obesity. The STEP 1 trial showed that there was a striking weight loss compared to placebo, with more than half of the participants losing 15% of their body weight from baseline during 68 weeks of treatment with semaglutide 2.4mg coupled with lifestyle intervention.

In STEP 2, researchers showed that when semaglutide was administered in combination with lifestyle intervention, there was a statistically significant greater weight loss of 9.6% achieved at 68 weeks with semaglutide 2.4 mg compared to placebo (3.4% weight loss) and 1.0 mg semaglutide (7.0% weight loss). STEP-3, which monitored the effect of once-weekly sc semaglutide 2.4 mg compared to placebo in 611 adults with obesity or overweight with comorbidities in combination with intensive behavioral therapy (IBT), also met the primary endpoint; showing a statistically significantly higher weight loss of 16.0% achieved with s.c. semaglutide 2.4 mg as an adjunct to IBT, compared to a 5.7% weight loss with placebo plus IBT after the 68-week treatment period[24]. STEP-4 had a unique study designed to show the positive effect of continued treatment with this approach. In this trial, the impact of semaglutide 2.4mg was monitored following a 20-week run-in period, after which the patients were randomly assigned to receive either semaglutide or placebo for the remaining 48 weeks. People who were switched to placebo after initial 20-week run-in period regained 6.9% of the body weight and who continued to take semaglutide lost a total of 17.4% of their total weight from the start over the whole trial[25].

Additionally, trials with this agent are currently ongoing, including the phase 3 SELECT trial, which will look at the effect of this therapy in reducing the risk of cardiovascular events in patients with overweight or obesity with existing cardiovascular disease (ClinicalTrials.gov, NCT03574597).

Given the range of available treatments for obesity, including metabolic surgery, as well as their efficacy and safety, it is important to individualize therapy and select optimal treatment regimens for individual patients [19, 21]. These include considerations in patients with cardiovascular disease, T2D, chronic kidney disease, depression, seizure disorder, psychiatric disorders and more. For patients with T2D, liraglutide, semaglutide, or other GLP-1 receptor agonists or SGLT-2 inhibitors should be considered; and in patients that use insulin, adding metformin, pramlintide, or a GLP-1 may be considered to mitigate against weight gain [26]. An overview of the efficacy and safety of treatment options for obesity is shown in Table 1 [27].

Drug | Weight Loss (placebo/drug) | Side effects |

Orlistat | -6.1% / -10.2% | Liver injury, gastrointestinal symptoms |

Phentermine | -1.7% / -6.6% to -7.4% (dose-dependent) | Palpitations, elevated blood pressure |

Phentermine/topiramate ER | -1.2% / -7.8 to 9.3% (dose- dependent) | Depression, suicidal ideation, cardiovascular events, memory loss, birth defects |

Naltrexone/bupropion SR | -1.3 / -5.0 to -6.1% (dose-dependent) | Seizures, palpitations, transient blood pressure elevations |

Liraglutide 3.0 mg | -2.6% / -8% | Nausea/vomiting, diarrhea, constipation, pancreatitis, gallstones |

Semaglutide 2.4mg | -2.4% / -14.9% | Nausea/vomiting, diarrhea, constipation |

Table 1. Summary of efficacy and safety of currently-available obesity pharmacotherapy

Tirzepatide and Emerging Approaches

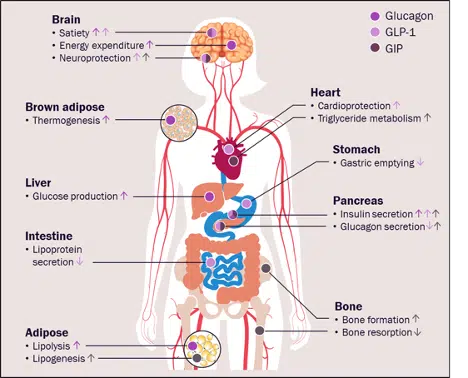

Besides the approval of semaglutide 2.4mg, much of the excitement in the field of obesity management also has to do with the approval of a dual GLP-1 and glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide (GIP) receptor agonist tirzepatide, which is currently approved for the management of T2D but has also shown promising results in the treatment of obesity in patients with and without T2D [28]. The rationale for exploring the role of this dual agonist comes from several preclinical and early-stage clinical studies, which suggest that peptide multiagonists such as tirzepatide enhance the metabolic effects seen with GLP-1 receptor agonists [29]. It is postulated that glucagon, GLP-1, and GIP elicit different effects in a variety of tissues, with most actions being complementary and potentially synergistic, and as such targeting them simultaneously can convey certain advantages compared to targeting one peptide alone (Figure 3).

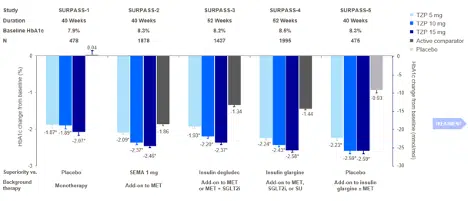

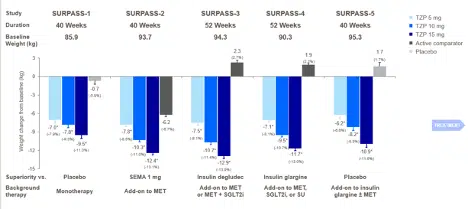

In light of this theoretical and early-stage framework, the phase 3 SURPASS clinical trials program is exploring the efficacy and safety of tirzepatide in patients with T2D (Figure 4), and results from some of these trials have been recently published. Across SURPASS trials 1-5, significant and dose-dependent reductions were seen with tirzepatide in both HbA1c and body weight (Figures 5 and 6). Due to the evidence from these trials, in May 2022, tirzepatide received FDA approval to improve glycemic control in patients with T2D as an adjunct to diet and exercise [37].

Several trials with tirzepatide are also ongoing, including SURPASS-6, SURPASS-J, SURPASS-AP, and SURPASS-CVOT, all of which will look at the effects of this agent compared to other agents (insulin lispro, dulaglutide, insulin glargine) on weight, HbA1c, and the occurrence of major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE), respectively [38]. In addition, the SURMOUNT phase 3 program will look specifically at the efficacy and safety of tirzepatide for the management of obesity [38]. Recently, data from the SURMOUNT-1 trial showed that tirzepatide treatment resulted in up to 22.5% weight loss in adults with obesity or overweight, who did not have diabetes at baseline [39]. The study met both coprimary endpoints showing greater improvement with tirzepatide in both percentage of weight loss and number of participants achieving at least 5% weight loss compared to placebo [39]. According to the data from SURMOUNT-1, tirzepatide appears to have greater efficacy in inducing weight loss compared to semaglutide 2.4mg, however, additional head-to-head studies are needed to solidify this claim.

Conclusions

The increasing prevalence and impacts of overweight and obesity in patients with T2D render weight loss and weight loss maintenance an important part of treatment goals. Nonetheless, clinicians treating patients with T2D often do not adequately address obesity, both in the suboptimal selection of anti-glycemic therapies that minimize weight gain or induce weight loss, but also in recommending comprehensive treatment strategies for the long-term management of obesity that include the utilization of the full spectrum of available therapies.

The benefits of weight loss in patients with T2D are substantial and are apparent with as little as 5% weight loss. As such, having a goal of at least 5% weight loss for patients with obesity and T2D should be standard as it can lead to clinically significant improvement. However, therapeutic inertia should be avoided; if patients on anti-obesity medications are not achieving 5% weight loss after 12 weeks, treatment plans should be adjusted adequately. Multiple anti-obesity drugs and interventions are available, including for long-term use, and are proven to help sustain weight loss better than lifestyle changes alone. Additionally, clinicians should focus on dedicating time to addressing obesity as any other chronic disease and discuss it in a nonjudgmental manner using patient-centered language.

- Davies, M., et al., Semaglutide 2· 4 mg once a week in adults with overweight or obesity, and type 2 diabetes (STEP 2): a randomised, double-blind, double-dummy, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. The Lancet, 2021. 397(10278): p. 971-984.

- Das, S.R., et al., 2020 expert consensus decision pathway on novel therapies for cardiovascular risk reduction in patients with type 2 diabetes: a report of the American College of Cardiology Solution Set Oversight Committee. Journal of the American College of Cardiology, 2020. 76(9): p. 1117-1145.

- Wang, L., et al., Trends in prevalence of diabetes and control of risk factors in diabetes among US adults, 1999-2018. Jama, 2021. 326(8): p. 704-716.

- Piché, M.-E., A. Tchernof, and J.-P. Després, Obesity phenotypes, diabetes, and cardiovascular diseases. Circulation research, 2020. 126(11): p. 1477-1500.

- Gregg, E.W. and L.A.S. Group, Association of the magnitude of weight loss and physical fitness change on long-term CVD outcomes: the look AHEAD study. The lancet. Diabetes & endocrinology, 2016. 4(11): p. 913.

- Lingvay, I., et al., Obesity management as a primary treatment goal for type 2 diabetes: time to reframe the conversation. The Lancet, 2021.

- Glauser, T.A., et al., Physician knowledge about and perceptions of obesity management. Obesity research & clinical practice, 2015. 9(6): p. 573-583.

- Kaplan, L.M., et al., Perceptions of barriers to effective obesity care: results from the national ACTION study. Obesity, 2018. 26(1): p. 61-69.

- Tomiyama, A.J., et al., How and why weight stigma drives the obesity ‘epidemic’and harms health. BMC medicine, 2018. 16(1): p. 1-6.

- Casanova, D., et al., Building Successful Models in Primary Care to Improve the Management of Adult Patients with Obesity. Population Health Management, 2021. 24(5): p. 548-559.

- Ciemins, E.L., et al., Diagnosing obesity as a first step to weight loss: an observational study. Obesity, 2020. 28(12): p. 2305-2309.

- Mawardi, G., et al., Patient perception of obesity versus physician documentation of obesity: A quality improvement study. Clinical Obesity, 2019. 9(3): p. e12303.

- O’Keeffe, M., et al., Knowledge gaps and weight stigma shape attitudes toward obesity. The Lancet Diabetes & Endocrinology, 2020. 8(5): p. 363-365.

- Ananthakumar, T., et al., Clinical encounters about obesity: systematic review of patients’ perspectives. Clinical obesity, 2020. 10(1): p. e12347.

- Luig, T., L. Keenan, and D.L. Campbell-Scherer, Transforming health experience and action through shifting the narrative on obesity in primary care encounters. Qualitative Health Research, 2020. 30(5): p. 730-744.

- Poku, C., B. Tahsin, and L. Fogelfeld, Weight loss: Lifestyle interventions and pharmacotherapy, in Obesity Hypoventilation Syndrome. 2020, Elsevier. p. 219-234.

- Singh, N., R.A.H. Stewart, and J.R. Benatar, Intensity and duration of lifestyle interventions for long-term weight loss and association with mortality: a meta-analysis of randomised trials. BMJ open, 2019. 9(8): p. e029966.

- Sumithran, P., et al., Long-term persistence of hormonal adaptations to weight loss. New England Journal of Medicine, 2011. 365(17): p. 1597-1604.

- Garvey, W.T., et al., American association of clinical endocrinologists and American college of endocrinology comprehensive clinical practice guidelines formedical care of patients with obesity. Endocrine Practice, 2016. 22: p. 1-203.

- Committee, A.D.A.P.P. and A.D.A.P.P. Committee:, 9. Pharmacologic approaches to glycemic treatment: Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes—2022. Diabetes Care, 2022. 45(Supplement_1): p. S125-S143.

- Association, O.M. 2021 Obesity Algorithm®. [cited accessed July 15, 2022.; Available from: https://obesitymedicine.org/obesity-algorithm/.

- Tak, Y.J. and S.Y. Lee, Anti-obesity drugs: long-term efficacy and safety: an updated review. The World Journal of Men’s Health, 2021. 39(2): p. 208.

- Abbasi, J., Semaglutide’s Success Could Usher in a “New Dawn” for Obesity Treatment. JAMA, 2021. 326(2): p. 121-123.

- Wadden, T.A., et al., Effect of subcutaneous semaglutide vs placebo as an adjunct to intensive behavioral therapy on body weight in adults with overweight or obesity: the STEP 3 randomized clinical trial. Jama, 2021. 325(14): p. 1403-1413.

- Rubino, D., et al., Effect of continued weekly subcutaneous semaglutide vs placebo on weight loss maintenance in adults with overweight or obesity: the STEP 4 randomized clinical trial. Jama, 2021. 325(14): p. 1414-1425.

- Apovian, C.M., et al., Pharmacological management of obesity: an endocrine Society clinical practice guideline. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, 2015. 100(2): p. 342-362.

- Müller, T.D., et al., Anti-obesity drug discovery: Advances and challenges. Nature Reviews Drug Discovery, 2022. 21(3): p. 201-223.

- Jung, H.N. and C.H. Jung, The Upcoming Weekly Tides (Semaglutide vs. Tirzepatide) against Obesity: STEP or SURPASS? Journal of Obesity & Metabolic Syndrome, 2022. 31(1): p. 28.

- Baggio, L.L. and D.J. Drucker, Glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor co-agonists for treating metabolic disease. Molecular metabolism, 2021. 46: p. 101090.

- Capozzi, M.E., et al., Targeting the incretin/glucagon system with triagonists to treat diabetes. Endocrine reviews, 2018. 39(5): p. 719-738.

- Rosenstock, J., et al., Efficacy and safety of a novel dual GIP and GLP-1 receptor agonist tirzepatide in patients with type 2 diabetes (SURPASS-1): a double-blind, randomised, phase 3 trial. The Lancet, 2021. 398(10295): p. 143-155.

- Frías, J.P., et al., Tirzepatide versus semaglutide once weekly in patients with type 2 diabetes. New England Journal of Medicine, 2021. 385(6): p. 503-515.

- Ludvik, B., et al., Once-weekly tirzepatide versus once-daily insulin degludec as add-on to metformin with or without SGLT2 inhibitors in patients with type 2 diabetes (SURPASS-3): a randomised, open-label, parallel-group, phase 3 trial. The Lancet, 2021. 398(10300): p. 583-598.

- Del Prato, S., et al., Tirzepatide versus insulin glargine in type 2 diabetes and increased cardiovascular risk (SURPASS-4): a randomised, open-label, parallel-group, multicentre, phase 3 trial. The Lancet, 2021. 398(10313): p. 1811-1824.

- Dahl, D., et al., Effect of subcutaneous tirzepatide vs placebo added to titrated insulin glargine on glycemic control in patients with type 2 diabetes: the SURPASS-5 randomized clinical trial. Jama, 2022. 327(6): p. 534-545.

- A quick guide to the SURPASS and SURMOUNT trials. 2022; Available from: https://diabetes.medicinematters.com/tirzepatide/type-2-diabetes/a-quick-guide-to-the-surpass-and-surmount-trials/18478154.

- Release, F.P. FDA approves novel, dual-targeted treatment for type 2 diabetes. May 13, 2022 May 19, 2022.]; Available from: https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-approves-novel-dual-targeted-treatment-type-2-diabetes.

- Min, T. and S.C. Bain, The role of tirzepatide, dual GIP and GLP-1 receptor agonist, in the management of type 2 diabetes: the SURPASS clinical trials. Diabetes Therapy, 2021. 12(1): p. 143-157.

- Jastreboff, A.M., et al., Tirzepatide Once Weekly for the Treatment of Obesity. New England Journal of Medicine, 2022.