A recent report released by the American Medical Association (AMA) Council on Science and Public Health evaluated the problematic history of using body mass index (BMI) as a health measure.

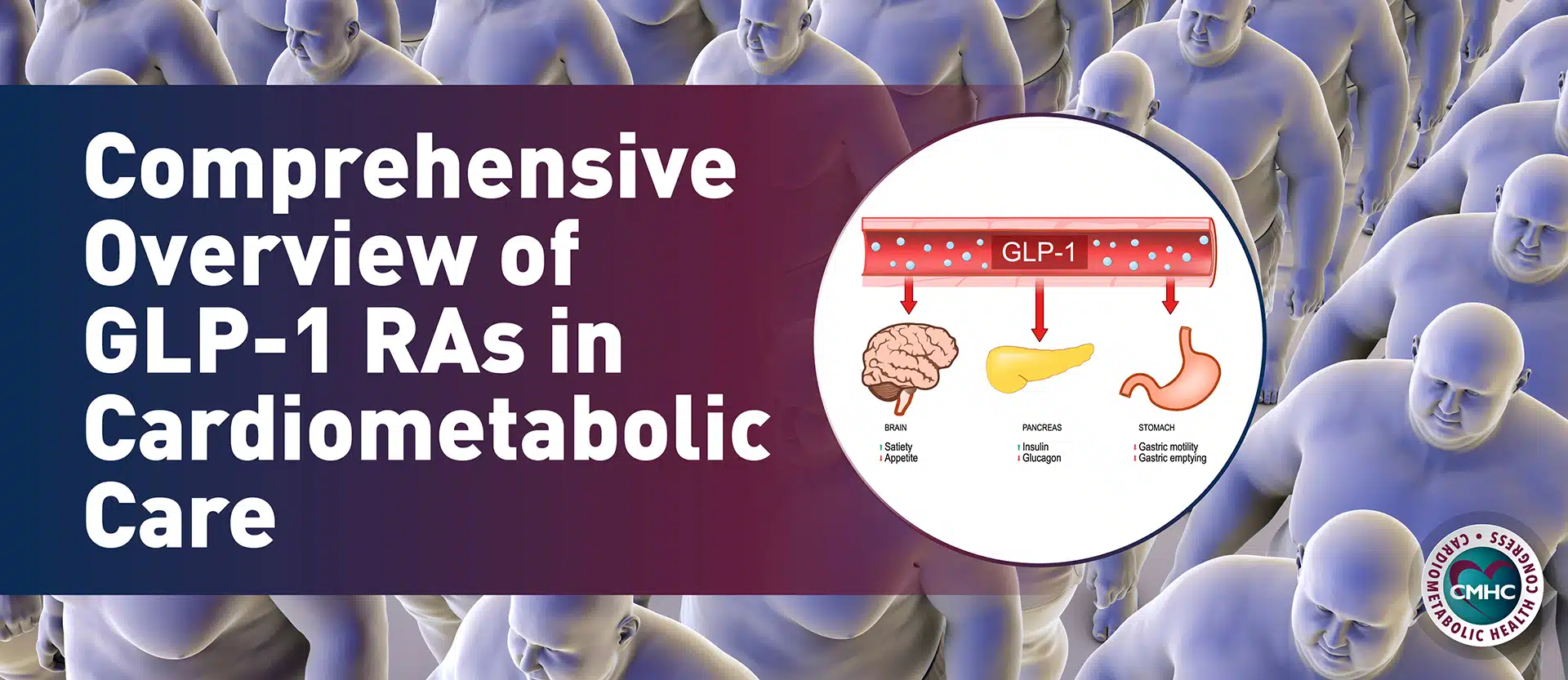

The delegates responsible for AMA’s new policy noted that BMI is helpful in determining health risks related to body fat at population levels but loses accuracy when applied to individual patients. However, because the council conceded that no better method of determining health based on body fat is available, they recommend clinicians use BMI in conjunction with other “valid measures of risk such as, but not limited to, measurements of visceral fat, body adiposity index, body composition, relative fat mass, waist circumference and genetic/metabolic factors.” The AMA’s action is in recognition of the issues with how the BMI measure was developed and used in medical history. The measure has a reputation of historical harm, racist exclusion, and notorious problematic development because it used data collected from non-Hispanic white populations.

Expert perspective

As an obesity medicine scientist and physician at Harvard Medical School, Dr. Fatima Cody Stanford has been a vocal advocate for recognizing the limitations and problems associated with using BMI as the sole measure of obesity. Dr. Stanford has highlighted that BMI is an oversimplified measure that does not account for important factors such as body composition, muscle mass, and distribution of fat. As a result, it fails to differentiate between fat and muscle, which can lead to inaccurate assessments of an individual’s health status. Dr. Stanford emphasizes the need for a more comprehensive and personalized approach to assessing health, one that considers individual factors. She has pointed out that the data on which BMI is based, perpetuates misclassification and disparities in certain ethnic groups with different body compositions.

As an obesity medicine scientist and physician at Harvard Medical School, Dr. Fatima Cody Stanford has been a vocal advocate for recognizing the limitations and problems associated with using BMI as the sole measure of obesity. Dr. Stanford has highlighted that BMI is an oversimplified measure that does not account for important factors such as body composition, muscle mass, and distribution of fat. As a result, it fails to differentiate between fat and muscle, which can lead to inaccurate assessments of an individual’s health status. Dr. Stanford emphasizes the need for a more comprehensive and personalized approach to assessing health, one that considers individual factors. She has pointed out that the data on which BMI is based, perpetuates misclassification and disparities in certain ethnic groups with different body compositions.

“BMI is not a measure of health, and it is rewarding to see that the AMA has recognized the importance of evaluating additional factors such as waist circumference when treating patients with excess weight.” – Dr. Stanford

The history of BMI

In the 1830s, economist and statistician Lambert Adolphe Jacques Quetelet sought to determine if a person’s weight and height could be used to calculate its deviation from the physical “ideal.” He devised an extremely simple formula he called the Quetelet Index (QI): divide a patient’s weight in kilograms by their height in meters squared. The problem with the QI was also simple: people are three-dimensional, not two-dimensional, and QI only considered two dimensions. Bear in mind, however, that Quetelet never intended his index to be used to measure a person’s health or wellness, he was only examining whether differing body types would constitute “deformity, disease or monstrosity.”

Then, in 1972, obesity researchers rebranded the QI as “body mass index” and concluded it was the best measure of body fat available. The newly coined BMI became a major tool used by insurance companies to exclude potential patients from qualifying for coverage because their preexisting condition (high BMI) made them a medical liability. There were several problems with this, the most obvious being the exclusion of coverage based on a flawed measure that was never intended to be used in the field of health care.

Obesity is a global epidemic, but its only endorsed measure is flawed

Some important factors BMI does not consider are:

- Waist circumference. Abdominal fat is linked to a higher risk of cardiometabolic disease because of the visceral adiposity’s proximation to the liver, heart, and kidneys. Two patients with the same BMI may have different fat distributions, and studies show that the patient with fat around the hips and thighs (rather than the waist) may have a lower risk of disease.

- Muscle and bone density. Muscle is about 18% denser than fat, and bone can be up to twice as dense as muscle, but this varies greatly depending on the bone. Genetics and physical activity level influence a patient’s bone and muscle makeup, yet BMI doesn’t account for these differences and the important implications of muscle or bone versus fat mass.

- Sex differences. Men and women can be healthy with different percentages of body fat. Men are considered to have obesity at a body fat percentage of 25%, while women can have up to 32% body fat before being classified as having obesity. Unfortunately, getting an accurate measure of body fat requires complicated tools, and BMI is still the easiest way to calculate a standard measure of body mass.

- Race and ethnicity. The measure of BMI was based largely on data from European men but is used to guide care across racial and ethnic backgrounds in both men and women. For instance, Black women have been shown to have no increase in disease-related mortality with BMIs up to 37, even though a BMI of 35 is considered in the obese range. Conversely, many patients of South Asian descent have diabetes and related comorbidities despite falling into a normal BMI range. These examples indicate that the measure of BMI isn’t appropriate for predicting risk in diverse populations.

- Stigma. Relying solely on BMI can perpetuate weight stigma and discrimination. People with higher BMI scores may face bias in health care settings, leading to suboptimal care and negative psychological impacts.

- Health heterogeneity. Health, genetics and underlying medical conditions vary by individual patient. Those with high BMI may be healthy, while others with a lower BMI may have underlying health issues. The complex relationship between weight, health and chronic diseases cannot be captured in a simple measure such as BMI.

Key takeaway

To successfully research and improve the disease of obesity and its serious comorbidities, the way obesity is measured should be clearly understood through the historical process that led to its worldwide acceptance. No drug, device, strategy, or index can be applied to a patient population without the necessary research data to support it. The shortcomings of the BMI scale are indicative of a larger problem in medicine, which is that members of racial, ethnic, and gender minorities are underrepresented in clinical research.

Sources:

- AMA adopts new policy clarifying role of BMI as a measure in medicine [Internet]. American Medical Association. [cited 2023 Jun 27]. Available from: https://www.ama-assn.org/press-center/press-releases/ama-adopts-new-policy-clarifying-role-bmi-measure-medicine

- About adult BMI [Internet]. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2022 [cited 2023 Jun 27]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/healthyweight/assessing/bmi/adult_bmi/index.html

- Garabed Eknoyan, Adolphe Quetelet (1796–1874)—the average man and indices of obesity, Nephrology Dialysis Transplantation, Volume 23, Issue 1, January 2008, Pages 47–51, https://doi.org/10.1093/ndt/gfm517

- Keys A, Fidanza F, Karvonen MJ, Kimura N, Taylor HL. Indices of relative weight and obesity. Int J Epidemiol [Internet]. 2014 [cited 2023 Jun 27];43(3):655–65. Available from: https://academic.oup.com/ije/article/43/3/655/2949547

- Moharram MA, Aitken-Buck HM, Reijers R, van Hout I, Williams MJ, Jones PP, et al. Correlation between epicardial adipose tissue and body mass index in New Zealand ethnic populations. N Z Med J. 2020;133(1516):22–32.